Images

Wangechi Mutu

"This second Dreamer," 2017

"This second Dreamer," 2017

Patinated bronze and wood

Edition 2 of 3, 2 AP.

Overall, 38 x 18 1/8 x 21 1/4 inches.

Wangechi Mutu

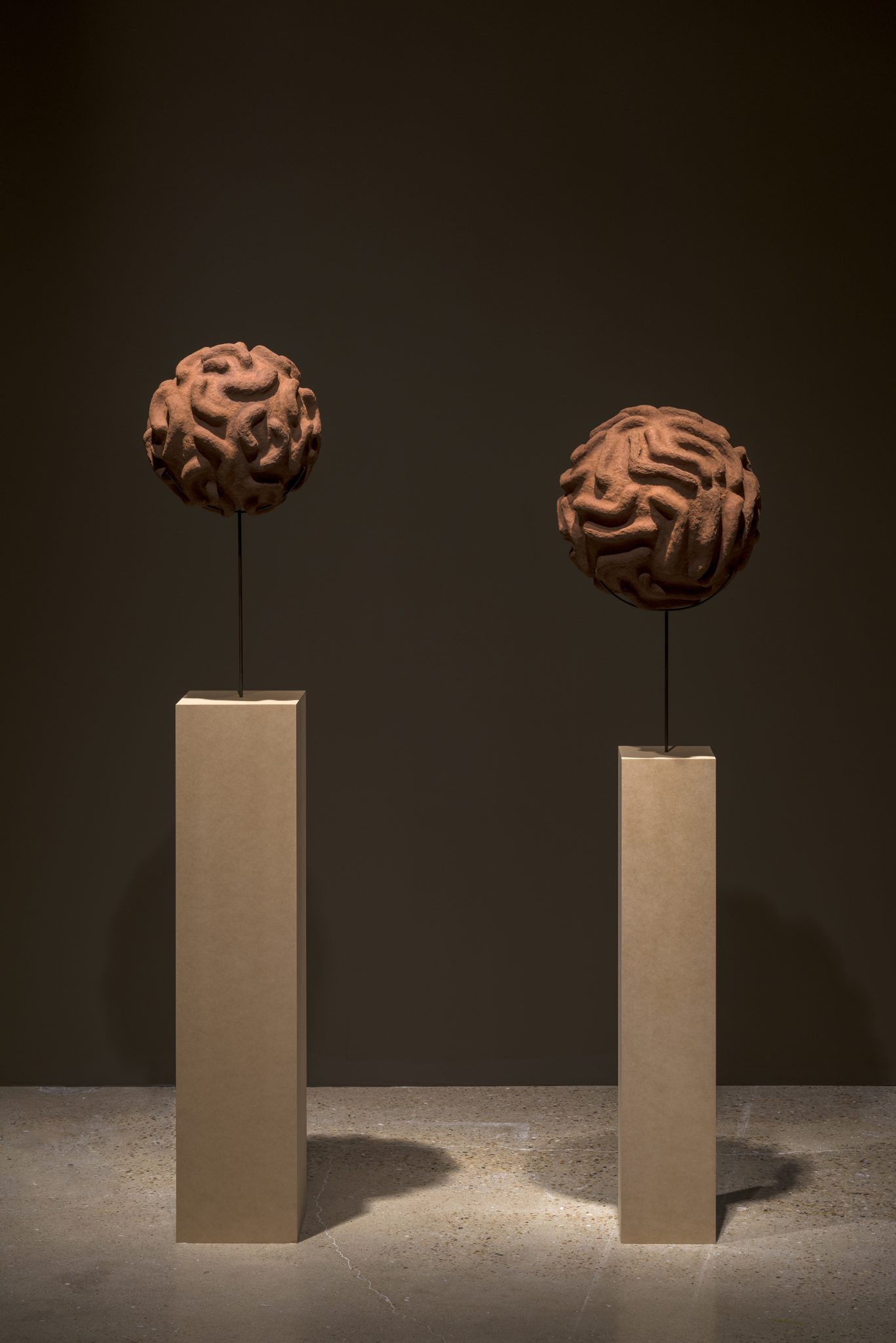

"Dengue Virus II," 2017, and "Dengue Virus," 2017

"Dengue Virus II," 2017, and "Dengue Virus," 2017

Red soil, paper pulp, and wood glue

Press Release

She gazes east across the lagoon, looking away from the approaching viewer, her ebony skin catching the sun and large tail curling behind her. Water Woman, 2017, a cast bronze sculpture by the artist Wangechi Mutu (Kenyan, born 1972 in Nairobi, lives and works in Nairobi and New York), sits perched atop a grassy mound at the foot of the amphitheater in the museum’s fourteen-acre sculpture park at Laguna Gloria. Rooted in myth and mystery, this siren figure—evocative of a mermaid—references both the dugong, an endangered relative of the manatee found in warm coastal waters from East Africa to Australia, and the East African folkloric legend of the half woman, half sea creature who entices and eludes (nguva in Swahili). The artist has said the nguva represents “bewitching female aquatic beings with powers to entrance and drown susceptible mortals.”1 In contrast to the ubiquitous Western iconography rooted in Hellenic, Nordic, and Anglo-Saxon depictions of silken-haired women with pale skin, here the siren is represented by the luminous, charcoal-colored female body, a vein of inquiry central to Mutu’s work.

Growing up in Nairobi in the 1970s and 1980s, Mutu noted that representations of people in film and television during her childhood primarily consisted of white men and women, and when they were black, they didn’t resemble urban African people.2 Likewise, referencing the colonialism and masculinity dominating historical and mythological narrative, Mutu has articulated that the nguva in African folklore was a cunning temptress, said to come out of the sea and masquerade as a human to “trick people,” namely persuadable men, in order to “utilize [her] power to drown people, to drag them into the ocean.”3 The gendered narrative of women as dangerous temptresses is ubiquitous throughout history—as in the extraordinary prosecution of women as witches across the U.S. and Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries—but in Mutu’s narrative, it is complicated further by the colonialism, slave trade, and identity endemic to African history. Perhaps because of this, Mutu’s Water Woman appears not dangerous but poised and melancholy, as if she has carried the weight of this history on her shoulders for centuries.

Mutu moved to the United States in 1992 to study art, earning her BFA from Cooper Union in 1996 and her MFA at Yale University in 2000. Since then, using a wide range of media including video, sculpture, performance, installation, and works on paper, she has generated an artistic practice centered around issues of ritual, race, consumerism, and the politics of identity. Her work weaves elements of East African mythology, as seen in the nguva, with Afro-surrealist elements of science fiction and fantasy, critiques of African and female stereotypes, and universal notions of power, race, and colonialism. Among Mutu’s best-known works are her magazine-based collages, begun in 2002 and continuing today, depicting grotesquely beautiful hybrids of female figures and animal parts with distorted lips, eyes, and heads. Her sculptures, installations, and video performances often incorporate organic materials, such as fur, fabric, plants, earth, water, and wine, while their gestures and actions imbue the work with ritualistic overtones and indirect critiques of the art historical canon. Mutu also mines the moving image, historically film but more recently video animation. The artist’s first spectacular foray in this animated vein, The End of eating Everything, 2013, is a lush composition featuring the singer Santigold as a fantastical, omnipotent Medusa-gorgon devouring everything in sight until she manifests her own self-destruction.

In 2016, Mutu opened a second studio in Nairobi, and this return to her “alien mother,” as the artist has referred to it, has catalyzed a transformation in her work.4 Fresh materials and methods referencing the Kenyan landscape—such as the distinctive rust-colored clay of Nairobi’s volcanic soil and a dark, coal-like paper pulp—evidence a shift in the artist’s focus from primarily two-dimensional works to the earthy, the organic, and the spiritual, with an emphasis on three-dimensional forms and performance-based installations, as well as the playful and imaginative opportunities of video animation.

In conjunction with the newly installed Water Woman at Laguna Gloria, Mutu premieres a solo exhibition of new and existing works at the Jones Center on Congress Avenue—her first major monographic exhibition in Texas since 2004, and her first solo exhibition in Austin. Anchoring the exhibition is a new, site-specific edition of Throw, 2017, an action painting generated by a performance in which Mutu throws black paper pulp against the wall, creating an abstract composition that dries, hardens, and then degrades over time. The three-channel digital animation The End of carrying All, 2015, is located just behind Throw, its fantastical Sisyphean narrative depicting an African woman walking up a hill as structures and cities increasingly, magically, pile up like buckets heaved on her head and back. Another work, This second Dreamer, 2017, a bronze female head with a braided crown that lies sleeping on a large wooden block, reclaims the appropriated African masks that influenced a generation of modernist sculptors (such as Constantin Brancusi). Also included in this exhibition are Mutu’s Prayer Beads series, large-scale strings of earthen beads evoking religious rosaries that seem to have risen from the Kenyan soil; Heelers, a series of anthropomorphic shoe sculptures; and various sculptures made of horns and wood. Tapping into the spiritual and supernatural, the ancient and primordial, and the terrestrial and cosmological, Mutu’s objects and installations propose a revised narrative of matriarchy and power, where the next generation’s history of art includes the African heroine.

1 Artist in email correspondence with the author, January 19, 2016.

2 Wangechi Mutu in 6 Artists on Black Identity, from Louisiana Channel, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 2016: http://channel.louisiana.dk/video/6-artists-black-identity.

3 Wangechi Mutu in conversation with Deborah Willis, BOMB Oral History Project, 2014, quoted in Adrienne Edwards, “Nguva na Nyoka,” exhibition catalogue, Wangechi Mutu: Nguva na Nyoka (London: Victoria Miro, 2014), n.p.

4 Artist in conversation with the author in Austin, Texas, November 2, 2016.

This exhibition is organized by Heather Pesanti, Senior Curator, with text also by Pesanti.